Jensen Huang told a conference in Dubai last week: “This is the beginning of a new industrial revolution. This is about the production, not of energy, not of food, but of intelligence. And every country needs to own the production of their own intelligence.”

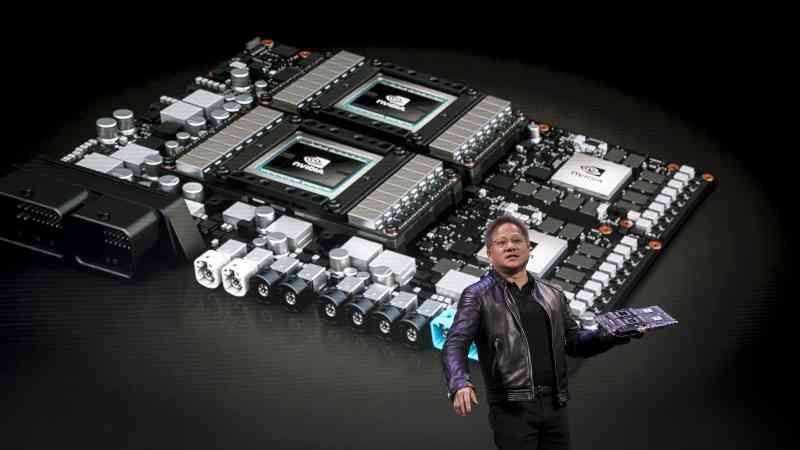

Crucially, Nvidia, the Taiwanese-born billionaire’s company, has positioned itself at the heart of this “revolution”. It makes the powerful graphics processing units that are used to train and run artificial intelligence models and demand for its wares has been insatiable, pushing its stock market valuation within touching distance of $2 trillion. Moreover, there is the promise of more where that came from. Huang promised that in the next six weeks he would reveal “a whole bunch of things we’ve been working on, the next generation of AI”.

Yet the company’s latest earnings announcement on Wednesday is set to be a key test of the Wall Street bet on continued demand for AI. Will Nvidia, as it has done so often already, deliver again? Or are some analysts right to warn that a bubble could be developing in the technology sector?

Started in 1999 by Huang, 61, Nvidia initially focused on graphics, putting pixels on screens in a sophisticated way. It was particularly dominant in the desktop computers graphics card market, serving customers such as Dell, HP and Lenovo, as well as Pixar, the animation studio. Later on, scientists realised that the cards could be used to power AI. And as other technology groups have pursued their own ambitions in AI, so they have come knocking at Nvidia’s door: Mark Zuckerberg said recently that his Meta Platforms group would be buying 350,000 Nvidia cards by the end of 2024, estimated to cost billions of dollars.

Such an appetite for the chips is reflected in investors’ hunger for the stock. Nvidia’s share price has risen by 225 per cent in the past year. It is now worth more than Amazon and Alphabet, the owner of Google, cementing its place in the so-called Magnificent Seven technology heavyweights of Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla. These stocks in turn have driven the recent outperformance of America’s stock market, which ended last year substantially higher, despite gloomy economic conditions and a sharp rise in interest rates to historic highs.

New York dramatically outpaced London, for example, where the FTSE 100 barely generated a positive return, even after including generous dividends paid out by its constituents. Last year the S&P 500 generated a total return of 26 per cent. The Seven contributed almost two thirds of those gains, according to an analysis by Howard Silverblatt, a senior index analyst at S&P Dow Jones Indices.

What the Big Seven share is not only the weight of high earnings expectations but also a claim to being able to capitalise on the rush to adopt AI by consumers and businesses. And since the start of this year Nvidia has been pushed to the forefront, driving almost half of all gains in the S&P 500 and offsetting tumbles in the share prices of Tesla, Apple and Intel.

The recent flotation of Arm Holdings merely confirmed this appetite for anything to do with AI. The Cambridge-based chip designer’s share price is up by more than 120 per cent since it went public last September, as investors bet that the hype around the technology will continue.

Venu Krishna, head of US equity strategy at Barclays, said that “upward earnings revisions for Big Tech continue to power earnings of the entire S&P 500”, yet he also warned that as the sector’s earnings dominance grows, so does its “concentration risk. We wonder to what degree the Street’s expectations for margin expansion [in the 2024 financial year], which remains fairly aggressive, will come to depend on just a handful of names carrying the broader US equity market.”

For its part, Nvidia has stunned the market again and again with its earnings figures, in November reporting revenue of $18 billion for the quarter, up 206 per cent year-on-year. This time the company is predicting revenue of $20 billion, plus or minus 2 per cent. Analysts are confident that Nvidia can continue its strong run. The shares trade at 34 times forward earnings, which puts the chipmaker at a higher rating than the likes of Apple and Microsoft.

That valuation might look punchy, but it could be less so if Nvidia can achieve the level of earnings growth that Wall Street expects. Factor in the earnings growth forecast for Nvidia over the next two years and it has a price-earnings growth ratio of 0.8, easily below the golden ratio of 1, below which a stock is generally considered good value by the market.

Not everyone is convinced that AI is a safe bet. The ever-rising technology stocks have led some critics to make the comparison between today’s AI-fuelled boom and the dotcom era, when technology stocks were driven to stratospheric levels between 1998 and 2000, only to crash back down to earth in the three years that followed. Some argue that the results could prove to be the monster under Wall Street’s bed and that a surprise shock from Nvidia could send the market into retreat.

“Markets are pricing the technology as if it is a paradigm shift, whereas it is really a continuum of what has gone before. It is a bit boring and should be in everything,” one investor said.

Albert Edwards, a veteran equity analyst with Société Générale and a former Bank of England economist, said that valuations of American technology stocks were now at extremes last hit as the Nasdaq bubble burst. “I never thought we would get back to the point where the value of the US tech sector once again comprised an incredible one third of the US equity market,” he said. “This just pips the previous all-time peak seen on July 17, 2000, at the height of the Nasdaq tech bubble. I cast my mind back to 2000, where the narrative around the IT bubble was incredibly persuasive, just as it is now.”

While the hype curve around AI soared in 2023, caution has emerged in 2024 in three key areas: copyright infringement, misinformation and regulation, which could curb enthusiasm around the stocks. Just before Christmas, The New York Times launched a lawsuit against Microsoft and OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, last year’s technology sensation, over copyright infringement, alleging that the powerful technology companies used its information to train their artificial intelligence models and to “free-ride”. Other content makers such as Getty Images have followed.

Since then, at the start of the global elite’s annual shindig at Davos, the issue of the technology being used to disrupt elections has been listed as one of the key global threats in the year ahead. Part of that discussion centred on regulation, “a balancing act and key risk”, according to analysts at Barclays. They argued that “for businesses looking to benefit from AI, significant hurdles to unfettered rollouts may arise on the back of these policy interventions. Governments may also need to intervene in the labour market if AI starts to impact the jobs market more substantially and quicker than anticipated.”

In addition, American export restrictions on sending high-tech chips or equipment to China would cause Nvidia’s sales to “decline significantly”, the company said in November.

Krishna warned that AI should be treated with caution, “given prior episodes of excessive tech-related exuberance”, but added that the technology was more than simple hype. “Over the long term, it is easy to see existing business being disrupted and new business models being created by AI.”

Like the breakout stars of technology that have gone before, Nvidia’s lofty valuation creates a high bar to surpass to provide further fuel for the stock’s rally. While headwinds are ahead for AI, most investors continue to bet that it will be a winner.